This is what humanity looks like

Tales from the soup run

For the past six years, Randeep and Nishkam SWAT have hosted a soup run on the Strand in central London. Four times a week, up to two hundred people congregate for hot food. But what they receive in dignity and community here is almost more important.

The red of rear-view lights stretches towards the horizon. We’re heading due east from Southall, a Sikh area of West London. From the front seats of the van comes the half-sung, half-spoken sounds of the sunset prayer.

This being London, it’s constantly interrupted by sirens, a buzzing motorcycle, a mobile phone going off. We roll through Edgware Road, then through Kensington, London’s boroughs passing the cultural baton along as we go.

The team load up at SWAT HQ, ready for their night run.

The team load up at SWAT HQ, ready for their night run.

The journey

We’re in one Nishkam SWAT’s many vehicles, named Compassion. Our destination: Central London. The Sikh charity has been running a homeless kitchen on the Strand since 2012. They set up four nights a week to dish out hot food, cooked up by local restaurants, families and spiritual groups.

“The week before last, we had the Jewish community come out with food,” Randeep, operations director for SWAT, tells me. “Last Sunday we had the Hindu community come out. That collaboration is the message we want to give out. As human beings, we walk on the same soil, we breathe the same air, we bleed the same colour blood, we just look different. That’s all it is.”

Randeep explains the SWAT blueprint.

Randeep explains the SWAT blueprint.

"Nishkam means selfless. That’s what we promote, selfless serving. That’s called sewa. It’s part of the Sikh belief. We’ve taken that out of the gurdwara and onto the streets. Most of us are third, or fourth generation British, so these are our streets. We’re here to serve our community.”

He’s made the mistake of querying someone’s need for food handouts before.

“Big mistake,” he says. “This woman broke down crying, saying she’s a working mother who's forced to decide between paying the heating bills or paying for food. I learned then that you can’t tell from people’s outsides what they’re battling with.”

Now, he questions no one.

Hot food pick-up at Punjab restaurant in Covent Garden

Hot food pick-up at Punjab restaurant in Covent Garden

The van feels far too wide for Covent Garden’s narrow streets, and as we park up outside Punjab restaurant on Neal Street, the sliding door opens to a world of noise. There’s the theatre crowd, the shopping crowd, the after-work drinks crowd. There’s embraces, laughter and frantic activity as the team spills out of the van and into the restaurant, returning with huge vats and baking trays whose smells erupt out to fill the van.

"Everyone is treated with respect."

"Everyone is treated with respect."

The next time the doors open, we’re outside Zimbabwe House on the Strand. A considerable queue is already forming. Next door to where we pitch up, there’s two barbers cutting the hair of all comers. Beside them is another group, handing out cold food. Some days, another crew comes along to pitch two mobile showers, free to use for anyone who needs one.

The fold-out tables are assembled. The SWAT jackets are pulled on. Steam rises from the vats into the cold night. Samosas are revealed beneath foil, and an enormous cake, piped with ‘Nishkam SWAT’ in red icing, is cut, ready for handing out.

Volunteers prepare and serve hot food.

Volunteers prepare and serve hot food.

Anonymous – I

I get talking to some of the men in the predominantly male queue. One such man implies his own way into homelessness: “There’s parents who’ve come over here, who are third or fourth generation, housed by the council, who have their children here. When the parents die, their children don’t own the house, and don’t have the money they need to buy the council house. Some children are just put out on the street.”

He goes on: “Winter is coming, and the majority of these people will be on the streets,” he says, gesturing to the crowds here. “They’ll be suffering from hypothermia, or death. Every week you’ll find somebody homeless dead. Some of them, they’ll go to the Thames, and they jump in. You don’t see those figures reported. They’re never public.”

“If you’re homeless, then you don’t have an address for a vote. And if you don’t have a vote, you don’t have a voice, and so they’re not interested in your opinion. That’s how it can perpetuate.”

He shows me his name in his passport, both corners missing.

A considerable queue forms as hot food is served

A considerable queue forms as hot food is served

Anonymous – II

Another man comes over, balancing a steaming coffee on top of a box of hot food from NishkamSWAT’s stand.

“I worked at the flag handover ceremonies of the London Olympics while homeless. I was a production volunteer for five months. They used to give us an Oyster card, so I used that to ride the night buses. That’s where I slept.”

Volunteering at the Olympics “really gave me a second life,” he says. “The motivation to be a good citizen has kept me away from drugs, alcoholism, gambling. That work gave me the motivation to become a role model.”

He still carries that from six years ago, he says. His CV is astonishing: having volunteered at the London Olympics, he’s worked at Lord’s cricket ground, and also got community funding to volunteer in Brazil at the Rio Olympics in 2016. All while homeless.

He continues: “This year, I got an unconditional offer to do a Masters’ at a university in London. I got a scholarship, but I’m still struggling with the finances.” When asked what he’s going to study, he tells me: “International Development Management. I hope to work for the UN.” The admissions officer, he tells me, was so impressed by how he’d got by that they’d extended an unconditional offer. “My credibility is based upon my character. Even though I have lost everything, I still have that.”

He leaves me with a piece of advice that has served him well: “Persevere, don’t give up, and it will come to you.”

He’s set his sights on Tokyo 2020 next.

Preda

Another man wanders over, wearing a Calvin cap and a sweater that reads “2017 is gonna be amazing!” The group around me greet him like an old friend, then he extends his hand to me. “Preda,” he says. He tells me how he broke his hand when hit by a car, couldn’t work, and subsequently lost his job. With no job he couldn’t pay the rent, and he’s now been living in a tent for a year. Like others before him, he’s upbeat and striving to do good.

“You can do good things without having money, without having a home,” he says. Then he turns to the spiritual as he describes his struggle to survive. “God does these things, expecting a reaction from us. It’s on us to make that a positive reaction, not a negative one. I’m trying to do my best.”

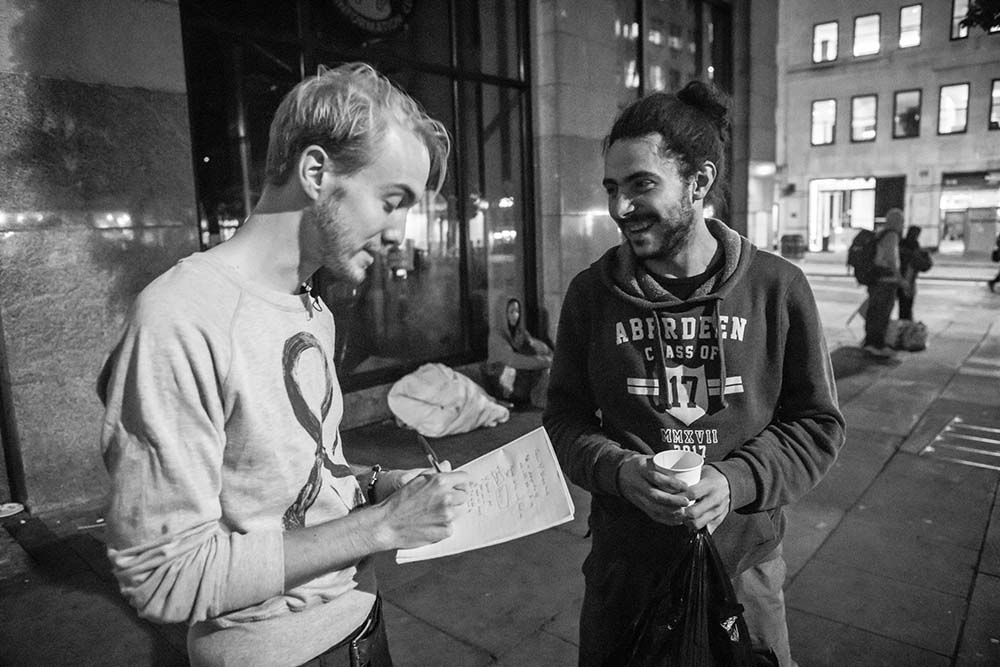

"It's good to have someone to share your emotions with."

"It's good to have someone to share your emotions with."

“I want to open a centre,” Preda says, “open 24 hours a day, where everyone is welcome, where there's volunteers and specialists. Many people in the street can’t afford a CSCS [Construction Skills Certification Scheme] card to start work again. They need a chance to restart, not to be stuck in these queues,” he gestures to the line for the soup run. “Some of the people,” he continues, “they work cleaning the streets, they work in hotels. They don’t have a place to live, but they keep going to work. Rent is so expensive: you have to suffer a little bit before you have the money for rent.” Then he spreads his hands, “but you get sick on the streets. You get attacked on the streets. A few weeks ago, I had to buy a new tent. Someone burned my old one. People think homeless people are bad people, but they’re not bad people. They’re just normal people.”

Our chat breaks off several times as others come over to say hello to Preda. I comment on the feeling of community around here. Those here are up on their feet, provided for without the need to beg, and among friends.

Preda agrees: “If somebody has a place to sleep, we don’t leave others in the street.”

Anonymous – III

I’m nudged in the direction of a man in a burgundy hoodie.

“They tell me you are a poet,” are his first words. “Me too. When I am sad, I write love poems or sad poems. I write them to keep them, but after 2-3 years I look at them and I think: what the f---?” We laugh, united over this writers’ quirk.

Poets on the street.

Poets on the street.

I ask him if there’s other poets on the streets. “I don’t know,” he says. “If you talk to people about your poetry, they laugh at you, and ask ‘what the f--- is this?’” He laughs, then his face stiffens.

“Because the world is sick now. In this world, love doesn’t exist.”

His words come from a background of loss – a father who died twelve years ago, a girlfriend who met someone new, a broken leg blowing the final whistle on a footballing career. He hails from Ramnicu Valcea, he tells me. When I don’t reciprocate his nodding, he grins and says: “You may know it as Hackerville.”

His house there is almost finished, he tells me, and he hopes to move home soon.

Packing up

An hour after we get there, the food has been distributed, the birthday cake is gone, and the queues have dispersed back into the London night. Preda is now in the barber’s chair, his cap momentarily lifted.

"It's such a collective effort."

"It's such a collective effort."

I step back onto the Strand: a place of theatres, of coffee houses and families eating pizza in chain restaurants, a place where the homeless slip between the cracks of the public’s conscience again.

It’s an odd feeling, later that night, to climb into washed sheets with a roof over my head. I lie awake for a long while, staring through the skylight at the passing clouds, lit by the moon. Somewhere in London, under the same moon, on his back in his tent, lies Preda.

"People think the homeless are bad. But we’re not, we’re just normal people.”

"People think the homeless are bad. But we’re not, we’re just normal people.”

This story was brought to you by Oliver Cable and Mark Green, if you have a story that shows real people doing good for society please contact: mark@nwmsltd.com